Sunday, 9 August 2009

Floodplain

Sunday, 2 August 2009

cases

I was supposed to be at Brighton Pride this weekend. Instead, I was kept at home, stricken with a sinus infection. I was sad to have missed the opportunity to see friends I haven't seen in a while, but secretly relieved to avoid the ritual meeting dance of the homosexual: the air kiss, the hair flick, the head tilt, and the inevitable exchange of gossip. It's not that I don't enjoy it - a little hate is excellent refreshment on a hot day - but I prefer it done with freshness and scandalous delight, instead of the prurient laundry list of peccadilloes and profanations relayed with an outrage which would be more convincing had I not seen most of my friends' livers crawl out their mouths for a rest from boozy embarrassment. There's also the additional benefit of not having to step over the twitching, drooling pile of jaw-grinding teenagers on the beach this morning, or trying to find a tolerable Bloody Mary in a town where there is neither any vodka left nor a single sober barman. The small things.

Sunday, 31 May 2009

MONUMENTS

What if I were to begin to speak about loss in a way that, really, doesn't seem to speak about loss at all? In the fourth Canto of the Inferno, Dante discovers four great shades who died before the Christian faith was established - Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan - who lead him to a great castle with seven walls, their perpetual dweeling place. The castle's courtyard - a green meadow, its greenness incongruous and mysterious in hell - is filled with the great and authoritative persons of antiquity, not only falcon-eyed Caesar, but the Muslim philosopher Averroes and Saladin brooding and apart. They speak but rarely, slowly, with great solemnity.

The passage is famous, perhaps most famous for the four great poets' recognition of Dante as their equal, or the incongruous Islamic sage; but prior to the entry to this castle, Virgil pales. Dante assumes that he pales from fear, but instead, Virgil says, he blanches from pity for the damned, 'e di questi cotai son io medesmo'. ['... and I myself am one of these.'] One might expect Dante to flinch or shy from the damned, even from Virgil, but instead he replies with affection, pouring out titles: 'dimmi, maestro mio, dimmi segnore.' ['... tell me my master, tell me sir...'] Such a moment, so early in the dream that is the comedy ('so full of sleep'), tells us much about Dante, the architect and chiosatore of the last judgement, who can both consign a pope to hell and listen with such stirring empathy to the story of Paolo and Francesca:

.... sì che di pietade

io venni men così com’ io morisse.

E caddi come corpo morto cade.

[... that for pity / I swooned as one dying / and fell down as a dead body falls.]

Paolo and Francesca's love is a whirlwind; the noble castle of the ancients is as static as a picture, suspended and motionless It is, as Dante says a place of neither sorrow nor joy (but the air is broken with sighing.) The castle, which is in some measure a place of exaltation for Dante, is also a place of privation. Tomorrow is the same as the tomorrow after that, and after that (eternity is very long, especially towards the end.) Augustine wrote that evil lacked an ontological status, that is, it was simply a privation or absence of good. That is the Limbo in which the greats of antiquity find themselves; in the lower parts of hell, evil is very much concrete, the torments precisely observed, here it is simply lack.

The castle is a monument to loss, and full of figures who have written or been written, alone in their washed-out histories, the catalogue of names that constitutes the end of the canto. At the other end of Christian history, closer to us, W.B. Yeats wrote a poem that seems, to me, to hear the same lack, 'News for the Delphic Oracle.' The poem runs:

I

There all the golden codgers lay,

There the silver dew,

And the great water sighed for love,

And the wind sighed too.

Man-picker Niamh leant and sighed

By Oisin on the grass;

There sighed amid his choir of love

Tall Pythagoras.

Plotinus came and looked about,

The salt-flakes on his breast,

And having stretched and yawned awhile

Lay sighing like the rest.

II

Straddling each a dolphin's back

And steadied by a fin,

Those Innocents re-live their death,

Their wounds open again.

The ecstatic waters laugh because

Their cries are sweet and strange,

Through their ancestral patterns dance,

And the brute dolphins plunge

Until, in some cliff-sheltered bay

Where wades the choir of love

Proffering its sacred laurel crowns,

They pitch their burdens off.

III

Slim adolescence that a nymph has stripped,

Peleus on Thetis stares.

Her limbs are delicate as an eyelid,

Love has blinded him with tears;

But Thetis' belly listens.

Down the mountain walls

From where pan's cavern is

Intolerable music falls.

Foul goat-head, brutal arm appear,

Belly, shoulder, bum,

Flash fishlike; nymphs and satyrs

Copulate in the foam.

The poem is in part a response to Yeats' own earlier poem ('The Delphic Oracle upon Plotinus') and partly a sickle-grinned parody to Milton and Spenser. Yet I think it is impossible not to also hear echoes of Dante here: in the first stanza, Yeats' paradise is barely disturbed by motion, save for that of his sighing philosophers and heroes. It is not too far a push, I think, to see these sighs as echoing the sighing around Dante's castle - but it's also the sighing of an exhausted race of statues and images. Like Dante's miscellany of authorities, these figures are also Yeats' philosophical and mythic forebears, now in a shimmering, bedewed and failing paradise.

The language has all the hallmarks of late Yeats - the vulgar codgers, the cynicism about the mystic images that sustained his earlier poetic vision, the cruel copulation that mocks a lofty tone. His heroes stretch, lie, yawn, but never speak, bounded by their own fading stories, they repeat and laze in post-coital exhaustion. Yet it's also a poem of animation: what reinvigorates the poem is Pan's intolerable, falling music, until the refined images slide headlong into polymorphous fucking, a host of (importantly) nameless nymphs and satyrs in foam.

Taken as a whole, the poem doubtless calls for a number of readings: the repudiation of the symboliste tradition and oneiric celticism of early Yeats, the renascent language of the vulgar and somatic, the violence that was Yeats' stock-in-trade and which made Auden and Eliot fear and admire him. But it is also a poem about history and loss. Yeats never really loses sight of the loss of love that constituted the basis for much of his earlier work: Yeats' paradise does sigh for love, which moves the sun and other stars, and this poem has to be read in concert with that driving obsession. This is a poem that opposes the long swathe of history to the ecstatic moment, taken out of history - thus the second stanza, where strangeness, violence and ecstasy merge and unify in a dance of repeated, reanimated passions that point to a dissolving moment which cannot be entirely contained within the structure of the poem itself. The 'laurel crowns' of the choir of love, the symbol par excellence of poetry as an achieved, formal effort are cast off as burdens before the ecstatic moment itself.

The poem is the reproof of Pan against Plutarch's narration (in the Moralia) that Great Pan is dead, but its violence, the slide of its sighing heroes into the foam, obscures its status as a poem. Any written pastoral, as Yeats knew, is subject to fraily, to the pathos of loss and distance; the Arcady here is one into which that distance and frailty already intrudes, and which is in the last moments of its dissolution. In Yeats, plenitude always gives way nightmare, and the torpor of his subjects falls back into the generative throng of Pan's music. I have said that its status as poem is what is most interesting to me here, and that is because it is a created object, a machine for memorialising loss: we its readers can forget that it is a textual mediation, lost in its vision and music; to Yeats, its author its status as object could never be fully occluded. The loss is endemic to the poem - nature's ecstatic victory over the painted figures of art, history and philosophy (sighing because they lack the tragic joy Yeats sees in the fluctuating ocean) is mediated, ironised, not quite fully captured, through a carefully-wrought piece of art.

In Borges' short story Ragnarök, the narration of a dream, the gods of Olympus, Egypt and Scandinavia return to life among human civilisation in the present day. The story is not long -- no more than a page - at first they receive homage and honour from the assembled crowds, but gradually the details of the bodies of the gods start to seem out of place, savage, and from their mouths emerges unintelligible speech, clicking, whistling, clucking, gargling. With the realisation that the gods are predators, the story ends with this line:

Sacamos los pesados revolveres (de pronto hubo revolveres en el sueno) y alegremente dimos muerte a los Dioses.

Hurley, in one of the better translations of the story, renders the lines thus:

We drew our heavy revolvers (suddenly in the dream there were revolvers) and exultantly killed the gods.

The line admits only the logic of dreams, and the parenthetical statement both notes and normalises that logic: 'suddenly', according to the logic of dreams, we were possessed of revolvers, the iconic statement of a violent humanity which has transcended the violence of our savage, old gods; 'suddenly', a connective form beloved of Dante, as Auerbach notes; 'suddenly' the dream turns to concretion as the heavy revolvers fall through the texture of nightmare, solid, sudden, real and violent.

This story has come a long way from Dante, and even, one might think, from Yeats. But what I see here is a trace of pathos, a way of thinking about literature as allowing an imaginative encounter with a desired object, but also tracing its fall, its failure - the space between dream and reality that literature fills. Dante: tant' era pien di sonno a quel punto - so full of sleep at the point where his journey begins. It is hard not to see the threads of dream running through it.

But Dante's dream of Beatrice - and I do not want to say that the Comedy is simply a dream for Beatrice, a monument to Dante's loss, but say that the poem is the dream, and the monument, and the vision and maybe infinite things otherwise - is an imaginative encounter, a dream of retention that is not a dream of retention because it is a poem and an artefact. Dante: 'lo non Enea, io non Paulo sono,' as neither Aeneas nor Paul, and yet both and more, through the underworld and above the third heaven.

If Dante engineered the comedy as, among its other infinite purposes, a form of imaginative recuperation, an all-encompassing dream and memorial in which he could author a meeting with her, then such a meeting is imperfect. At first humiliating, penitent, confessional for him, later, his last glance at Beatrice in the Empyrean is riddled with loss:

Così orai; e quella, sì lontana

come parea, sorrise e riguardommi;

poi si tornò all'etterna fontana.

[So did I pray; and she, so distant / as she seemed, smiled and looked on me, / then turned again to the eternal fountain.]

Borges called these 'the most moving lines literature has achieved', and I do not wish to fuddle them with clumsy explanation. Dante, looking at the immeasurable rose of the just, in the Empyrean with Beatrice at his side, turns, suddenly, to find her gone and an Elder standing where she stood. He cries 'Ov'è ella?' - where is she? And she, in a halo of glory, in the rose, is Beatrice, lost to him, and he prays to her, saying 'per la mia salute / in inferno lasciar le tue vestige.' She who, in hell, left footprints for his salvation. But that is what Beatrice is, through the dream of the Comedy: footprints.

The commentators on this passage say that this is Dante's movement from reason into faith, that he does not utter a word after she withdraws because all earthly residue in him is destroyed. I think, yes, this is true in one sense, in that the story of spiritual transformation does reach its end, the wheeling love of the Empyrean does transform our poet -- and yet, and yet, there is something in those lines that tells us about the failure of the other story, the story of Beatrice and Dante, that in his dream, even in his imagination she seemed so distant, so imperfectly captured, and she turns, and turns away forever. She is always only footprints.

It is trite to say that the poems of dreams and paradises are always distant memories of what is lost to us, trite because it is only partly true: because they are not only memories but monuments, and like the architecture of monuments, trace out that loss, memorialise loss and what was lost, make it alive to be lost again. What if I were to end this from a text that is not a poem at all, but another essay on loss?

Charles Lamb, in 'Dream-Children: A Reverie', writing under the name of 'Elia', tells the story of his brother, James Elia, who has recently died, to his children. As he wends his way through the story of a family, of his brother's kindnesses and harshnesses, the children respond with joy or sorrow, sometimes up on their knees with excitement or crying with despair, until he looks into the eyes of his daughter and sees in her the vivid and total representation of her mother, Alice. Yet Alice, like Beatrice for Dante, was the love that Lamb never attained, and gazing into the eyes of his never-to-be child, their faces fade until they become only a voice, only a speaking loss:

....“We are not of Alice, nor of thee, nor are we children at all. The children of Alice call Bartrum father. We are nothing; less than nothing, and dreams. We are only what might have been, and must wait upon the tedious shores of Lethe millions of ages before we have existence, and a name”—and immediately awaking, I found myself quietly seated in my bachelor armchair, where I had fallen asleep, with the faithful Bridget unchanged by my side—but John L. (or James Elia) was gone forever.

Saturday, 21 March 2009

Tarnac Nine

'she likes her face in all the papers; everyone knows her by name'

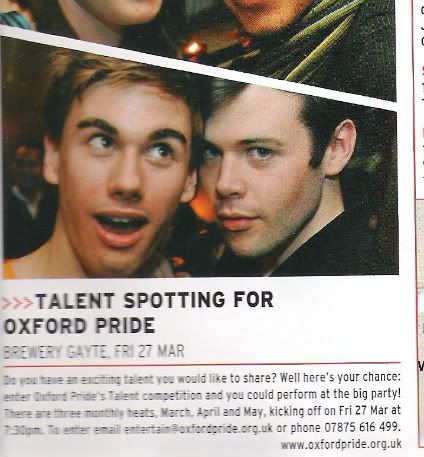

Flipping through some local homo rag, none could be more surprised than me to find my image - a particularly serious one at that - being used to promote Oxford Pride. Surprised or joyous-looking expression on boy to my right courtesy of innumerable gin & tonics in easily breakable plastic cups at preceding LGBT gathering. Said gin always served with a tangible air of bitterness and recrimination, in a striplit dungeon deep in the bowels of one of Oxford's more illustrious colleges.

Flipping through some local homo rag, none could be more surprised than me to find my image - a particularly serious one at that - being used to promote Oxford Pride. Surprised or joyous-looking expression on boy to my right courtesy of innumerable gin & tonics in easily breakable plastic cups at preceding LGBT gathering. Said gin always served with a tangible air of bitterness and recrimination, in a striplit dungeon deep in the bowels of one of Oxford's more illustrious colleges.